Are curiosity and wonder endangered species in modern health research?

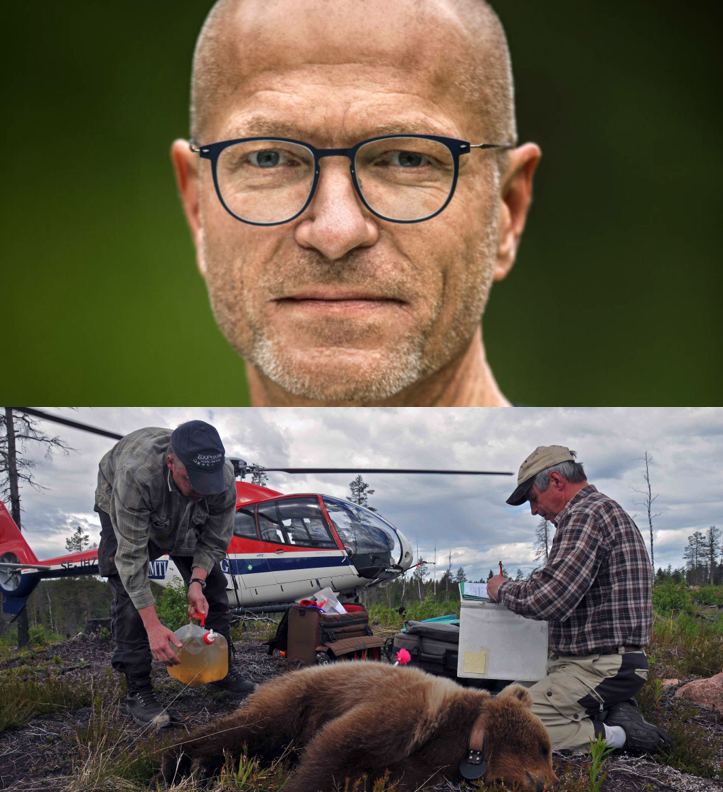

With very limited external funds, Professor Ole Frøbert has spent 13 years studying the bear's defense against blood clots and has recently published the results in Science. He calls for a new model for research funding that paves the way for major breakthroughs.

At the heart of all major scientific breakthroughs lies curiosity and wonder. From Galileo's gaze at the stars to Darwin's investigations of nature's diversity, it is these qualities that have driven science forward.

But has research - and perhaps especially health science research - become too uniform and conformist, and does the Nordic model for research funding stand in the way of new major breakthroughs?

This is the view of Ole Frøbert, professor at the Department of Clinical Medicine at Aarhus University, who has just had his latest research result published in Science.

In this, he and his research group describe how the physiology of the brown bear protects it against blood clots during hibernation - a potential first step towards a groundbreaking treatment against blood clots in humans.

And Ole Frøbert's approach to research is as unusual as his choice of subject.

"This is an uncharacteristic research project. We have searched without knowing exactly what we were looking for. We have not been able to draft detailed research plans with milestones and partial results. Many major breakthroughs have arisen in this way, but the strategy is not supported in the Danish model for research funding, which in my opinion is idea-killing and leads to conformity," he says."

No support for unpredictable research

Ole Frøbert refers - without comparison otherwise - among other things, to Alexander Fleming's discovery of penicillin and AU’s most recent Nobel laureate Jens Christian Skou's discovery of the sodium-potassium pump in cells as examples of wild and experimental research projects that would likely have been denied funding in today's Denmark.

Fleming, a Scottish biologist, stumbled upon the power of penicillin while studying bacteria in his laboratory. The physician Skou discovered the mechanism of the sodium-potassium pump by studying 20,000 shore crabs from the Kattegat.

“This type of research is increasingly being marginalized by the current system for research funding, and very few foundations support this kind of open and unpredictable research. The consequence is that many potentially groundbreaking ideas do not receive support, or researchers give up applying in advance,” says Ole Frøbert.

Rejection after rejection

Even with his remarkable work, Ole Frøbert's bear research team has become accustomed to rejections of applications for research funds.

He and his team have sent numerous applications in both Sweden and Denmark. Only a very few have been successful, and only for small amounts for specific equipment from smaller and local foundations - far from sufficient to keep the bear research team going.

The team has instead been driven by dedication to the project and has had to work with the limited resources they have had at their disposal.

“We have really lived hand to mouth and improvised all the time, because there are constantly unforeseen expenses, when we for example had to go and take samples from the bears and spend 70,000 kroner on clearing snow. How do you convince a foundation that it is smart to spend money on? It's not every day that you come across an application with the budget item 'helicopter fuel',” says Ole Frøbert.

Quantity over quality

He believes that today there is too much focus on quantity in research - a system that often rewards the number of publications rather than the quality or originality of the work performed.

The way applications are assessed today, according to the researcher, has led to a change in behavior among applicants. And when there are specific and uniform criteria for getting money, it changes the entire approach to research, believes Ole Frøbert, who today sees a large overrepresentation of particularly one type of research project.

“There has been a massive development in epidemiological research, which is often faster to carry out and easier to get published. Although this type of research has its justification, it rarely leads to new and groundbreaking knowledge,” he says and continues:

“An abundance of data and a flood of publications does not necessarily mean that we are moving forward. On the contrary, they can steal resources and attention from more risky and potentially revolutionary research projects.”

Research should teach us something genuinely new

Ole Frøbert mentions, among other things, studies that investigate the relationships between diet and disease as examples of research that is highly prioritized in Denmark and the rest of the Nordic countries. Both because we have unique databases that make such research possible, and also because this kind of epidemiological research attracts many foundation funds.

"It results in publications and impressive annual reports, but that's not what we should use the research for. We should use research to learn something genuinely new," says Ole Frøbert.

When Ole Frøbert and his team of German and Swedish research colleagues published their latest research result last month, it created a lot of attention in both Danish and foreign media.

Both the perspectives of having shown the way towards a new, risk-free and effective treatment for blood clots in humans and the story of a research team that has spent 13 years translating the sleeping winter bear's physiology to humans fascinated readers and viewers in nationwide media.

The publication in Science and the broad interest in the work is a reminder of how important it is to support experimental projects, believes Ole Frøbert.

Calls for a new model with room for risk

He calls for a system where there is room to take chances, and which does not punish researchers for going on an exploration journey within their field.

It could possibly be a model where a percentage of public funds is earmarked for "high-risk" projects - those that do not necessarily guarantee a payout, but which have the potential to lead to groundbreaking discoveries.

Applications should also to a lesser extent be judged on detailed research plans and more on overarching research questions and the potential for new major discoveries, Ole Frøbert believes.

"Many of the biggest breakthroughs have come from researchers who have had the freedom to follow their curiosity, no matter where it led them. If we want to see new major breakthroughs, we need to give researchers the freedom to take chances and explore the unknown."

Contact:

Professor and head consultant Ole Frøbert

Aarhus University, Department of Clinical Medicine, Ørebro Universitetshospital

Phone: +46 730895413

olefro@clin.au.dk